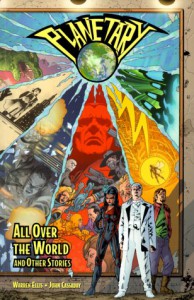

I think the Planetary series by Ellis and Cassaday may be one of the most ambitious, and certainly most enjoyable, comics (excuse me, I mean graphic novels!) that I have ever read. It is yet another post-Watchmen, post-Dark Knight meta-textual exploration of the genre, but manages to be one that doesn’t lose its sense of humour or sense of wonder as it dissects some of the weird, wonderful, and even silly elements of the genre…no small feat! Also, Ellis does not restrict himself solely to an examination of the world of superheroes as it’s been portrayed in the funny books, but also includes a myriad of other pop culture genre tropes in a heady brew that’s chock-full of pulpy goodness! Conspiracy theories meet the world of metahumans, the science of the occult and the magic of super-science rub shoulders with genre standbys, and a world of strangeness and wonder slowly unfolds like a snowflake.

The premise is pretty simple, and kind of ingenious given Ellis’ aims: it’s a strange world, but the powers that be have been covering up every weird, wonderful, strange and scary thing that has reared its head in human history. Enter Planetary, an inter-continental organization of “archaeologists of the impossible” whose avowed goal is to unearth the secrets from which the enlightened ones would shield us and broadcast them in their yearly publication, kind of a Whole Earth Catalog of the weird and strange. The field team for Planetary is composed of three main agents: Elijah Snow is a gruff and taciturn leader who also sports the ability to generate cold on a superhuman level, Jakita Wagner the beautiful and nigh-invulnerable superwoman, and the Drummer, a prototypical slacker-geek whose ability to interface with anything electronic is truly extraordinary. Oh, and since this is a graphic novel/comic book I should note that the art by John Cassaday is consistently extraordinary, some of the best I’ve ever seen, really! I’ll break down the individual issues below and try to avoid any heinous spoilers.

Issue 0 (Preview) - “Nuclear Spring”: A secret military base; a genius cold war scientist decades ahead of his time; a quantum bomb that is able to rewrite the nature of reality; a friend of the scientist’s caught in the blast zone during the final test. What mysteries will the Planetary team find when they crack open this decades-old secret of tragedy and transformation?

Issue 1 - “All Over the World”: Jakita Wagner recruits the misanthropic loner Elijah Snow to join a mysterious team called Planetary. Details on their operations and make-up are scarce. They have scads of cash, but all the field team seems to know is that they are funded, and ultimately directed, by a shadowy figure known only as “the Fourth Man”. The organization’s aim? To uncover the mysteries that the powers that be want kept secret. Despite his suspicions and doubts Elijah decides to come along for the ride (a paycheck of a million dollars a year doesn’t hurt either) and on his first mission witnesses the uncovering of a decades-old secret base of operations for a team of heroes the world didn’t even know existed. We have a literal round table of pulp hero analogues: newly minted characters who are stand-ins for Doc Savage, The Shadow, Tom Swift, Fu Manchu, Tarzan, Operator 5, and G-8. I love this stuff. Homages to the great icons of pulp and comic book heroes are the kind of thing I eat up with a spoon, primarily, I think, because while the ideas behind these icons are fantastic the execution of their stories often leaves something to be desired (often either because the company that owns the properties doesn’t want anything ‘bad’ (read interesting) done with them, or simply because they were written into formulaic and kind of crappy stories by mediocre writers). Those problems can be remedied in this kind of ‘elseworlds’ context and Ellis proceeds to do so both here and throughout the Planetary series with panache. Love it.

Issue 2 – “Island”: Welcome to Monster Island! (Well, Warren Ellis’ version of it anyway.) What do you get when you combine an isolated and remote island populated by creatures out of a

Kaiju film, government cover-ups, and Japanese death cults? You get issue 2 of Planetary. Pretty good stuff that helps widen the lens beyond superheroes and show us just how strange Ellis’ secret history for his world really is.

Issue 3 – “Dead Gunfighters”: We continue our tour of Ellis’ strange world with another one-off tale centring around a ghostly cop in Hong Kong out for revenge and yet further hints about the ‘quantum reality matrix’, the snowflake, that underlies all of the strangeness being catalogued by Planetary. Think John Woo meets the X-Files.

Issue 4 – “Strange Harbours”: This, and issue 5, are where things really started to gel for me with Planetary; things began coming together and the “oh shit, that’s cool” moments were multiplying fast and furious. In this issue the team investigates the hole left after a single office building in the middle of a New York City block is vaporized. It seems as though something was unearthed by mysterious forces under the direction of people unknown and an investigator for the Hark corporation (the name will have meaning once you’ve read this far in the series) will be changed into something wonderful and strange. What does a homesick starship meant to fly between realities do when it’s been trapped under the earth for millennia? Recruit a new crew for starters. Captain Marvel (the Shazam version) meets Flash Gordon with a dash of the many worlds theory thrown in for good measure.

Issue 5 – “The Good Doctor”: Secret societies from the French Revolution with a breeding plan for superhumans, a Man of Brass (or is it bronze?) who devotes his life to saving a world that does not know he exists and collecting together similarly endowed individuals in the hopes that together they can solve the world’s ills, a pulp fiction extravaganza highlighting the glories and the dangers of thinking you can save the world. Elijah Snow’s suspicions have been accumulating since he joined Planetary and now he goes to talk with Doc Brass, saved in issue 1, to help clear his head. Things will start to roll from hereon in.

Issue 6 – “It’s a Strange World”: Now we get to the meat of it. What if the cold war space race was nothing more than a smoke screen for what was really happening behind the scenes? What if four astronauts (the number is important and the corollaries are very cool) were sent into the void and met up with forces unknown, forces that could transmute mere humanity into something more? What if they were the most evil sons of bitches you’re likely to meet and had both the will and the power to take the reins of the secret organization that had been keeping everything strange and wonderful from surfacing in the daylight world? What if Planetary finally found out about them? This issue single-handedly made the Fantastic Four a cool concept, something they hadn’t been, for me at least, well, um, ever. It also helped to answer the question that might nag any self-respecting comic book nerd who really thought about the whole concept behind the Fantastic Four (or science-based superheroes in general) as superhuman adventurers who discover the secrets of other worlds and realities: why doesn’t any of that gleaming gosh-wow tech ever filter down to the man on the street? Why don’t they have a cure for cancer? Where are the flying cars, dammit?! Well, it’s because the ‘superheroes’ are keeping it all for themselves, dumb-ass!

One thing that really worked well for me in this series overall was the way in which Ellis balanced between the self-contained one-off stories that were compelling in and of themselves with a greater story arc that made the journey all the more satisfying. He didn’t always manage to pull this balance off perfectly (sometimes the one-off tales seemed a little light, or the connections they had to the wider context weren’t sufficiently drawn, and occasionally the bigger story arc seemed a little bit rushed, especially at the very end), but overall he did a pretty exemplary job with this. Kudos! The sense of mysteries to be uncovered and of an answer greater than the sum of its parts (as gosh darn cool as those parts may be) was very well-played and, unlike some genre fiascos that have attempted the same trick (I’m looking at you X-Files and especially you Lost), Planetary mostly lived up to its potential in this regard. It looks like Ellis had mapped out his ideas and goal from the beginning instead of just engaging in some half-assed attempt to retroactively join together the disparate elements that were all thrown into the soup willy-nilly at the last minute. I love, love, love this series…and there’s more to come! Can I squee? Well, I will anyway. Squeeee!

1

1